In this there is an underlying assumption that we identify

candidates [as art] by subsuming them under a definition. That definition is one that many philosophers

have supposed we possess, if only implicitly, and that we apply to candidates

tacitly. Successive Theories have

attempted to recover it and make it explicit.

Clearly, a certain view of the nature of concepts underwrites all these

attempts. Concepts are regarded as

essential definitions. That is, concepts

are taken to be definitions that supply necessary and sufficient conditions for

membership in the category they designate.

Art is a concept; so, the story goes, the concept of art must have

necessary and sufficient conditions for application to particular instances. Noël

Carroll , Philosophy of ART,

Routledge (1999) pp250

The concept of ‘art’ has

evaded, scholars, artists, academics, critics and philosophers from the time

the first caveman placed a hand print on a cave wall. Most of the problems lie with those who fail

to consider what goes into making art but let’s look at what a concept of art

entails. Fundamentally a concept is an abstract idea; it is an archetypal

construct that sets limits that help us perceive and identify certain species

as being of a kind. As I have mentioned

in previous posts, it is a categorial term (meaning having to do with

categories). Our task now is to unpack

the notion of art to discover what conditions are necessary and what are

sufficient to allow us to recognize when something is or is not a work of art.

Understanding the Art ‘Form’

'Form'

is a term that is widely used by practitioners of the arts and it is the key

term for understanding the concept of art. Theatre practitioners, dancers,

musicians, visual artists, sculptors commonly refer to their activity as taking

place within an art form. When asked

what art form they work in they readily answer without confusion. They know

that Theatre is an art form or Dance is an art form. Indeed, when speaking of their work it is not

unusual for them to just speak of their form.

How is it such diverse practitioners can use the same concept - art form

- to describe their work? What is common

between theatre, the visual arts, dance, music and sculpture, et al that allow

us to describe them with the same concept? It has long been held that a statue

does not share anything in common with a theatre production or a novel but the

argument is wrong and most practitioners of the arts know it. But Noël

Carroll finds this argument somewhat specious for he attacks the view

that something is art only if it possesses and exhibits form.

But this is

extremely unhelpful. It does not provide

a necessary condition for art, since there are artworks – like the monochrome

paintings of Ad Reinhardt, Yves Klein and Robert Ryman – that have no

parts.(they are blocks of single colors.)

Moreover, reading the formalist’s theory in this way would defeat any

hope of his securing a sufficient condition for art, since everything that has

parts probably has form in the loose sense, and not everything is art.”(121)

Carroll

is trying hard but he has missed the mark.

What he fails to recognize is that not only do all art works have parts they also have aspects.

Aspects of Art

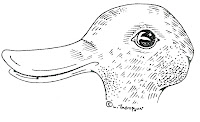

A sketch similar to the above diagram which

was first used by the psychologist Jastow and made famous by the philosopher

Ludwig Wittgenstein, is known as the duck-rabbit figure. Wittgenstein argued that you only see the

duck or rabbit in the diagram if you are already conversant with the shapes of

those two animals.

Wittgenstein was at pains to point out that the duck and the

rabbit are not two pictures. Rather they

are one diagram with two aspects. An aspect is a point of view. You may view the diagram as a duck or you may

view it as a rabbit. You may also see

both aspects simultaneously which is the situation of someone who was not familiar

with both the shape of a duck and rabbit.

I offered this example to help clarify the notion of aspects for all

works of art have aspects but unlike the duck/rabbit diagram works of art have three aspects.

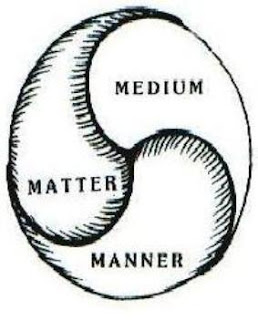

Aristotle

noted over two thousand years ago that tragedy had three aspects which we can

describe as the manner of presentation, the medium of presentation and the

object of presentation. Aristotle used

the term imitation rather than presentation but Aristotle’s use of the term

imitation does not merely mean a copy or likeness. Aristotle understood we could imitate things

that never before existed. While

imitation is a perfectly good term as Aristotle understood it, I have changed

it to presentation to avoid confusion. I have changed object to matter, meaning

subject matter. Aristotle believed that

form was contained within an object which provided us a means of identifying

it. What Aristotle failed to mention was

that all works of art contain a

medium of presentation, a manner of presentation and subject matter of

presentation. These represent the three

aspects of an art work and help us identify its art form.

Just

as we may attend to the duck aspect in the diagram above ignoring the rabbit we

may attend to the subject matter in a painting, sculpture, dance, theatre

production or any other art form ignoring the other two aspects. These three aspects are the aspects of form

that Carroll missed. Each aspect of a

particular art form has its individual constituent parts determined by the

medium used which in turn limits the methods and techniques that may be applied

(the manner). Artists are forever

searching out new mediums which demand different methods and techniques. The diagram below relates to the theatre but

it shows how the different parts of a theatre production are contained within

the different aspects of a theatre production.

This

diagram represents the art form of theatre.

In the theatre Aristotle recognized that the manner of presentation

deals with such things as set, costumes, lighting design, masks and make-up,

acting, movement, voice and speech

techniques, performing methods and styles as well as the design of the theatre

and stage. Clearly this list is not all

inclusive and not all parts are used in every production but it sets out the

types of things included in the manner of presentation. Obviously such things as voice and speech

techniques will contribute to characterization which is a part of the subject

matter of a production. The thing to

remember is that the medium, the manner and the matter along with their

constituent parts allow us to distinguish one art form from another. For the most part it is the medium that

determines the art form we are looking at but Literature and Theatre share the

same medium which is language however they differ in their manner of

presentation. (This is one reason play

scripts are studied in literature courses.)

It is not unusual that persons will go to the theatre to watch the

characters and involve themselves in the plot but seldom concern themselves

with how the lighting is accomplished and the effect it has on characterization

or setting or if the make-up is effective, over-done or lacking in some

way. Generally audiences only notice

such things if they are striking. They

seldom make it a point to evaluate what they believe to be commonplace. Often they are not conversant with such

things as costume and lighting design or set design. Seldom do they realize

that a touring set has to be designed differently to a set designed for a

particular theatre. Much as a person not

conversant with the shape of a rabbit, say, will not see the rabbit in the

diagram above, audiences who are not conversant with the demands of set,

costume and lighting design will not see nuances or the subtle shades of

meaning in these constituent parts of a

theatre production.

Failing

to recognize that works of art have three aspects limits our ability to

understand the concept of art. This was

the problem Carroll confronted when he insisted that the monochrome works by

artists such as Ad Reinhardt and Yves Klein have no parts and consequently no

form. A 1956 work of Reinhardt is like

the one below and seems to the uninitiated to be merely a blue rectangle. It’s a small work about 9 inches by 4 ½

inches.

The

size of the work should lead us to suspect something different is going on with

Reinhardt’s painting and when we discover that Reinhardt’s medium was Gouache

(pronounced g’wash) painted on photographic paper we are able to admire the skill of the artist. Gouache is a watercolor paint used with a

binder (probably gum Arabic). Gouache

will not allow the glossy whiteness of the paper to show through. Pigments in the gouache will lighten in the

drying which makes Reinhardt’s accomplishment even more impressive. It’s possible that he applied more than one

coat. We aren’t told how the paper is

mounted but this would be a significant consideration as the binder may have a

deleterious effect on the paper. Yves

Klein’s Blue painting is oil on canvas on wood.

In both cases the medium is significant to the manner of presentation

and consequently the subject matter.

Yves

Klein developed (with a group of chemists) and patented his own special

ultramarine blue which he called IkB.

Suspended in a synthetic resin it maintains its color wet or dry. For

Klein it was the purest of blue. Today

we recognize several types of blue; Cobalt, Prussian, azurite or ultramarine

are the most well-known. Blue pigment

has a special significance for artists; it was one of the most difficult and

most expensive pigments to come by for it has always been a synthetic pigment

first developed by the Egyptians. For

alchemists of the 14th century it was pigment valued as highly as

gold. Blue lapis lazuli from Afghanistan

ground to a powder was put through a difficult and demanding process until a

pigment called ultramarine emerged. It

wasn’t until late 1800 that an industrial process was invented which brought

down the price of this valuable pigment.

In

most of our art forms how they are presented; the frame chosen for a painting

or how it is lighted are a significant part of the manner of presentation.

After all, a painting in a pitch darkened room reflects no color at all and

cannot in situ be described as a work of art.

Below

is a similar diagram for the visual arts but as medium is the defining

characteristic of an art form we need to recognize that an oil painting is a

different art form from fresco which is a different art form from water color

which is a different art form from tempera, etc. Each of these different art forms use

different techniques, methods and tools as part of their manner of presentation

though they all may show us the same subject matter from the same point of

view. What is important is that all art

forms share common aspects but differ in their constituent parts. Clive Bell asserted that “…either all works

of art have some common quality, or when we speak of ‘works of art’ we gibber.” Bell, Clive, Art, Capricorn, New York (1958) pp17.

The

important point here is to remember that the medium used greatly affects the

end product. Different mediums require

different techniques and often different tools to embellish the work. Consider this exercise below which was

accomplished with several different mediums.

To Be continued…..

Launt Thompson

http://www.amazon.com/s/ref=nb_sb_noss?field-keywords=Launt+Thompson&url=search-alias%3Daps&x=16&y=9

No comments:

Post a Comment